I’ve had the opportunity to deliver a presentation to Procter & Gamble’s then-CEO, A.G. Lafley, four or five times in the decade he held that position. The first time was unforgettable. That day I learned a valuable lesson—the hard way—about how not to present to the CEO.

I’d been given twenty minutes on the agenda of the Executive Global Leadership Council meeting. This group included the CEO and a dozen or so of the top officials in the company. They met weekly in a special room on P&G’s executive floor designed just for this group. It’s a perfectly round room with very modern features, centered on a perfectly round table. Even the doors are curved so as not to stray from the round motif.

My presentation was the first item on the agenda that day, so I arrived thirty minutes early to set up my computer and make sure all of the audio/visual equipment worked properly. I was, after all, making my first presentation to the CEO. I wanted to make sure everything went smoothly. The executives began filing into the room at the appointed time and taking up seats around the table. After half of them have arrived, the CEO, Mr. Lafley, entered the room. He walked almost completely around the table, saying hello to each of his team members, and—to my horror—sat down in the seat immediately underneath the projection screen . . . with his back to it!

This was not good. “He’ll be constantly turning around in his seat to see the presentation,” I thought, “and probably hurt his neck. Then he’ll be in a bad mood, and might not agree to my recommendation.” But I wasn’t going to tell the boss where to sit, so I started my presentation anyway.

About five minutes in, I realized Mr. Lafley hadn’t turned around even once to see the slides. I stopped being worried about his neck, and I started worrying that he wasn’t going to understand my presentation. And if he didn’t understand it, he certainly wouldn’t agree to my recommendation. But I wasn’t going to start barking orders at the CEO to turn around and look at my slides. So I just kept going.

At ten minutes into the presentation—halfway through with my allotted time—I noticed he still hadn’t turned around once to look at my slides. At that point, I stopped being worried and just got confused. He was looking right at me, and was clearly engaged in the conversation. So why wasn’t he looking at my slides?

When twenty minutes had expired, I was done with my presentation, and the CEO hadn’t ever bothered to look at my slides. But he did agree to my recommendation. Despite that success, as I was walking back to my office, I couldn’t help but feel like I’d failed somehow. I debriefed the whole event in my head wondering what I had done wrong. Was I boring? Did I not make my points very clear? Was he distracted with some billion-dollar decision far more than whatever I was talking about? But then it occurred to me. He wasn’t looking at my slides because he knew something that I didn’t know until that moment, which was this: if I had anything important to say, I would say it. It would come out of my mouth, not from that screen. He knew those slides were there more for my benefit than for his.

As CEO, Mr. Lafley probably spent most of his day reading dry memos and financial reports with detailed charts and graphs. He was probably looking forward to that meeting as a break from that tedium, and as an opportunity to engage someone in dialogue—to have someone tell him what was happening on the front lines of the business, to share their brilliant idea, and to ask for his help. In short, for someone to tell him a story. Someone like me. That was my job during those twenty minutes. I just didn’t know it yet.

Looking back, it was probably no accident Mr. Lafley chose the seat he did. There were certainly others he could have chosen. He sat there for a reason. That position kept him from being distracted by the words on the screen and allowed him to focus on the presenter and on the discussion.

Mr. Lafley taught me a valuable lesson that day, and probably didn’t even know it. My next such opportunities involved fewer slides, more stories, and were far more effective.

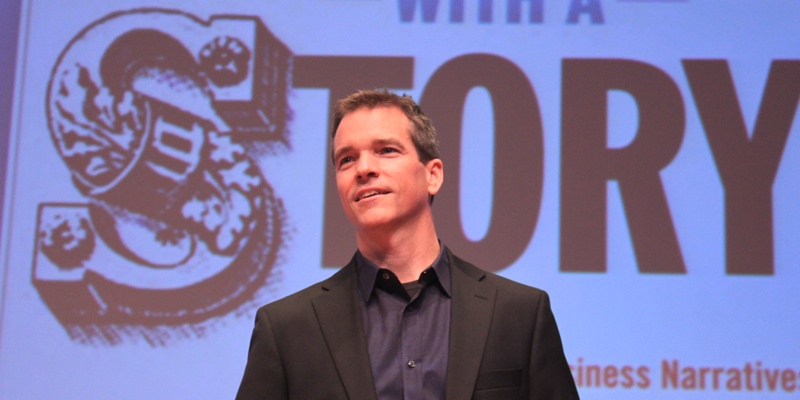

Interested in learning more about storytelling? Connect with Paul on his website: Lead with a Story

Used by permission. Original post April 16, 2012

Lead with a Story: A Guide to Crafting Business Narratives that Captivate, Convince, and Inspire, by Paul Smith

© 2012 Paul Smith; All rights reserved.

Published by AMACOM Books

Division of American Management Association

1601 Broadway, New York, NY 10019